- Home

- Poole, Josephine

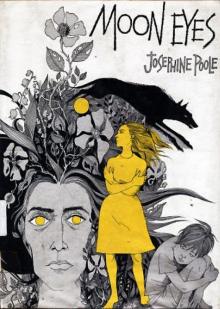

Moon Eyes

Moon Eyes Read online

JOSEPHINE POOLE

MOON EYES

Illustrated by Trina Schart Hyman

An Atlantic Monthly Press Book

Little, Brown and Company

BOSTON * TORONTO

* * *

Copyright © 1965, 1967 by Josephine Poole

Library of Congress catalog card no. AC 66-10547

OCR from fifth printing

OCR version 1.0

* * *

For my children, and for all children

with a battle to fight.

* * *

There’s a voice of the wild in the woods, a voice of the wild

Through bars, with the brown underfoot and the trees stripey green,

And a whistle for dogs, skulk dogs, dogs that come running

To creep, cringe dogs, of a pitchy skin, moon-eyed...

* * *

Table of Contents

Cover

Front Matter

Table of Contents

Part One - Waiting

Part Two - Whistling

Part Three - Dancing

End Matter

PART ONE

Waiting

Once upon a time there was a gray house, made out of stone in the shape of an L. Between a village and some woods a narrow road ran below the garden, which had a wrought-iron gate with the name of the house worked into it: Hurst Camber, meaning wooded eminence. It opened on to some steep steps, and a graveled path branching right to the front porch, left to the kitchen door. On the left was the kitchen garden, still kept up with espalier fruit trees, asparagus and raspberries; but Mr. Beer, whose wife looked after the house, had no time to do the formal grounds on the right as well. They had been laid out with care in the days when a good deal of thought, as well as money, was spent on the making of a landscape. And it was all jealously enclosed by a stout beech hedge even from the front path, so that no strange eyes could covet the treasures of Hurst Camber.

The long back of the house was built into the hill, which meant that on one side there were no ground-floor windows and those on the first floor were only a couple of feet above field level. Even on sunlit days it was rather dark inside, without a prospect from most of the downstairs rooms, as they looked straight into the hedge. This made the path seem narrower than it really was, smelling in summer of insects and dust, while winter winds rattled its twigs and hanging leaves. It was a private garden, full of corners and secrets. (But Mrs. Beer's cottage, further up on the common, had a bird's-eye view of the place.)

The hill had been chopped straight down to wall the length of the grounds, which it did rather roughly and frowningly however, standing underneath you could look up and see an edge of gay grass and dandelions, fringed against the sky.

Hurst Camber had belonged to Pawleys for a couple of hundred years. Mr. Pawley had once been a popular artist. He still wore the corduroy trousers and velvet jacket he had bought in his Chelsea heyday, but he did not exhibit in London any more. His wife had given him a daughter, later a son; and then had died. Now he found it difficult to paint. He started on a picture, all browns and grays, like winter in his garden. It was his work for three years, balanced hopefully on the three-toed easel in the drawing room, with a linen curtain to draw down when he was not frowning over it, worrying how to get on with it, his masterpiece.

Then came a particularly long winter, bitterly cold. And he could not bear, poor Mr. Pawley, another spring shut up between the hills. So he packed some painting things and an extra pair of socks into a cardboard suitcase, and told his children that he had to get away.

“What about us?” asked Kate.

Mr. Pawley pointed out that of course they must stay at home, as she had to go to school.

“I could leave.”

“Nonsense,” said her father, “and, anyway, you can’t come because you would be in the way. Look at this picture,” he cried, twitching at the linen draped over it, “it isn't finished, it never will be finished, unless I can get away! There's no spirit in me, Kate.”

Kate was truly sorry for him; but she also knew that her father's artistic temperament was reinforced with a will of iron, and that he had every intention of going away for the spring as he had already packed his suitcase. She was a practical girl and she did not waste breath in useless arguments. Besides, she was devoted to her father, and agreed that a change of scene would probably do him a great deal of good; and she rather liked the idea of having the house to herself for a few weeks.

“When are you going?”

“Tomorrow. There is a bus to Exeter tomorrow afternoon. And I have fixed up with Mrs. Beer, she will come in every day; and you know you can always ask her to stay overnight, she's very willing. She'll look after Thomas while you're at classes, but it's only six weeks to the start of the Easter holidays. And it'll be spring,” he wished, staring out at the sky that was grim with the sucked out hollowness of January into February.

So he left the following afternoon, and the children had the house to themselves.

At first it seemed very large, and cold and silent in the evenings. For three days wind filled the valley, running wild like an animal. It hunted down over the blue meadows, that were striped across and across with long black shadows, as if they had bones humping up under the grass; it entered the woods, making them flap in brown and green flags; it whisked the whole landscape into movement, and made the earth race with reflections of the clouds it pelted through gun-gray sky. Those nights, the house nearest the woods seemed to be balanced in a giant pair of hands, rocking and knocking, with a tapping and drumming of finger ends against doors and windows, so that every board creaked and loose bricks tumbled down inside the huge old chimneys. During the day it was exciting but after dark Kate and Thomas did not like to look out of the windows in case their house had broken away from the firmly rooted garden, up, up into a limitless rush of air. Mrs. Beer said she had never known such a wind.

But a brightly colored postcard came from St. Ives, saying that all went well with Mr. Pawley.

And Easter did come; and so, at last, did spring.

Kate lay in the dampish grass under the cherry tree, counting the flowers in the long lawn: “Cow parsley, clover, stitchwort, forget-me-nots.” The sky was bird's-egg blue, and not a cloud sat in it; Kate sang, and a cuckoo sang, and the Pawleys’ yellow cat, stalking along the top of the wall, crumbled off small pieces of mortar with his velvet underfoot, his slinking thief suit glaring like buttercups in the sunlight. “Dandelions, buttercups, celandine and daisies, goosegrass and lady's-smock . .”

All of a sudden, Kate was aware of a peculiar noise. It was a sort of hollow humming; and it did not come from any particular place, but as though everything in the landscape, even each blade of grass, was joined quivering into a strange reverberation. It was not loud enough to startle or even surprise her particularly; but the yellow cat was startled, all right, and acted most surprisingly. He shot off the wall, ears back and tail out straight; he fed into the house as though a dog was after him. And he was a secretive, self-controlled cat as a rule, but he ran right over Kate where she lay under the cherry tree as if he could not see her, and was gone in a moment.

She was supposed to read The Ancient Mariner these holidays, and she pulled out her copy of it from underneath her: its pages were grass-stained and badly creased. It was bent open:

Day after day, day after day,

We stuck, nor breath nor motion;

As idle as a painted ship

Upon a painted ocean.

She rolled onto her back, closing her eyes. The verse perfectly described her mood these Easter holidays. The weather was beautiful, not too hot, but everything shone: she dreamed in a golden garden. As idle as a painted ship upon a painted ocean. And it

was perfect here, in this little cultivated patch between the hedges and the wall. It was like being inside a beautiful flowery box, under a safe lid of cloudless spring sky.

That was a most peculiar sound still going on; as though the earth had suddenly turned into a huge humming top, she thought -- no, now she knew exactly what it was like. Last Christmas they had had wine, in the best crystal glasses, and her father had shown her how to make the glass sing by running a damp finger round the rim of it. This was just like being inside a singing wineglass, the whole bowl around one vibrating on a single, hollow note.

Next minute the noise had gone, and she turned back the pages of The Ancient Mariner to start at the beginning again.

Mrs. Beer loved many things -- housework and tea, and a line of clean clothes drying the length of her garden, primroses and making cakes and her quiet husband. But most of all she loved talking, and Thomas.

She was stuffed tight with conversation; and at the least excuse, out it came in a steady stream. Who had been born and who had died, who had married wearing what, how herbs had cured when surgery failed, the content of the sermon at last Sunday's prayer meeting with her own comments on it, tales of her relations and friends of friends, and her own dramatic experiences, all mixed up with dreams she had had, and medical advice: yet she was no scandalmonger, and went many times willingly from her bed to help with a dying person or a sick child.

She lavished affection on Thomas Pawley. He was a quiet, detached little boy but sometimes he would put his short arms round her ample waist to hug her; and since he had learned to walk would bring her presents: daisies at first and shiny stones from the path, then half an empty blackbird's egg, or some walnuts that had fallen in their mushy black cases from the tree on the lawn. He drew pictures for her, remarkably good pictures (Mr. Pawley shook his head and said he feared there was another artist in the family). He did not play much with toy cars or engines, but he would spend hours sitting on the floor, cutting paper into complicated shapes. He knew how to pleat it, cut the figure of a bird, perhaps, or a man, and then pull it out to make a whole string of flying birds or dancing men. No one had taught him -- he found it out for himself.

When he was two and a half, and making no attempt to talk, Mr. Pawley took him to Exeter, to see a famous specialist. He was told that there was nothing to prevent him from speaking quite normally. Thomas understood very well, and as he grew he seemed to be intelligent, but he would soon be five and still he did not talk. Mrs. Beer put it down to the shock of losing his mother at such an early age.

He loved Mrs. Beer, and his father, but most of all he loved Kate. She spoke for him and believed in him, sometimes she was cross but always she admired the things he made. This morning he went to find her, to get her in for lunch.

The only way into the garden was through an arch cut out of the living hedge, and here he stood for a few moments, taking in the colors. On his left was the wall, about eight feet high, but beautiful now with great bright mats of rock plant hanging down it; in the corner it made with the house stood the flowering cherry tree, under which lay his sister, rather fat and crumpled, chewing a bit of grass and reading. There was a birdbath on this part of the lawn, and behind it a grassy bank with bulbs whose yellow and white trumpets were beginning to wrinkle and turn brown. Flagstones set across the lawn led between the bulbs, dark rhododendron bushes and a spinney of larches, to his favorite part of the garden, which was cunningly laid at a lower level down a little flight of steps; and they branched right, past the walnut tree, into a corner that was also out of his sight, where there was a rose bower and a wooden garden seat. His mother had sat there often, and no one liked to go there now: the roses had not been pruned for years. Thomas stood under the archway impressing inside him every detail of the garden: the birds about the cherub who held up a shell of water for their bath, and the swing his father had fixed ten years ago for Kate from the looped branch of a great cedar; and then he went and stood over Kate and, as she was still intent, put his foot gently over the open pages of her book.

“Lunch, I suppose,” said she with good humor, scrambling inelegantly to her feet and dusting a few leaves and blades of grass from her cotton skirt. But Thomas took her hand, and they crossed the lawn instead.

A smell of damp and violets grew. They pushed between the overgrown rhododendrons and went down three stone steps; a thrush had been using one as his chop ping block and it was dusted with crushed snail shells. On either side of the steps stood a giant stone urn, spilling over with purple rock plant. And there at their feet lay Thomas's delight: a rectangular pool, with water lilies, and a spout on a rock in the middle of it. There was a paved path around three sides, while at its far end the natural wall of the hill had been built out into a rockery. Across the water from where they stood, the downward slope of the hill had been banked up and planted with azalea bushes; on their left, lilies of the valley carpeted the earth below the rhododendrons; and the whole secret place was screened from the road by the stout beech hedge and a spinney of larches, tall as church pillars, whose branches opened in a cloud of new green, while violets grew among their roots.

There were no goldfish now in the pool, and no fountain, for the spout had broken. The rockery was choked, a little more every year, by ground elder, and brambles whose streamers dipped into the water. The edges of the paving stones were marked out with weeds, and the violets straggled among larch cones and needles that had not been cleared for years. Only the trees exulted. And the lilies had increased to a carpet of green points almost ready to open, and hang out each a line of bells.

The water, full of dead leaves and twigs, reflected some blue sky. There where the rockery entered it, in a doubled amount of purple and yellow so that it was hard to tell what was plant and what reflection, was a slab with a small stone statue on it, of a boy looking into his cupped hands. Once he had looked at something, but whatever it was had been broken off and lost. He was weatherworn and patched with pale lichen; but his face had not been spoiled, and he stood looking down absorbed, detached. He reminded Kate of Thomas.

And this end of the garden was so overgrown, and overhung, that unless a person went to it through the grounds of Hurst Camber he could not know that it existed. Which made what they found then, odder than ever.

The children stood on the steps for a few moments, and then Kate walked round below the azaleas. She found a twig and lifted the edges of the lily leaves with it, in case a family of goldfish still survived among their slimy stems. What a fascinating world, she thought, bending down; the pond was exceedingly dirty and in summer would have a definite smell, but the cool yellow-green water was full of swimming spiders and strange long pale wavy weeds, scraps that looked like twigs suddenly produced sets of legs and scuttled away, and a quantity of minute brown particles shimmered like dust motes in a sunbeam. It was all surprising, a natural experiment; she poked about, idly enjoying herself, and at the same time she was conscious of bits of Thomas's reflection, like a jigsaw scattered among the flotsam of the pond. He was a stout, slow-moving little boy: now he crouched peering among the stones that built up the rockery, collecting snail shells and laying them out in line behind him on the path. Suddenly he straightened up, and stared.

“What's the matter?” said Kate. He was staring at the little stone statue, and she noticed again how very like it he looked, especially now standing so still, with such a solemn face. She walked back round the pond: there were no stepping-stones across it.

“What are you staring at?” And then she saw. Somebody had been writing round the base of the statue, scratching words into the gray stone, through the patchy lichen.

“Well, who on earth's done that?” she exclaimed. “How beastly of them. What does it say?” She bent forward over the pool, grunting with effort, and screwing up her eyes. The easiest way to read it would have been to wade into the pool, but they never had waded it. It wasn't deep, they had poked sticks down as far as it went often enough; but it was anoth

er thing to take shoes off and wade in. It was such a full pond, of weeds and lilies and rocks and various water life; besides, perhaps the goldfish had got bigger, and were living secretly in the mud on the bottom. So Kate bent and twisted and strained her eyes rather than wade the pond (although she was in danger of falling bodily into it); and she was able to read the words written round the statue, because although the letters were not large, they had been made recently and whitely scarred the stone.

“'First we'll wait, then . . . we'll . . .' Wait a bit, I'll have to go round the other side. '. . . we'll . . . whistle . . . then we'll dance together.' Whatever does it mean? It doesn't make much sense. 'First we'll wait, then we'll whistle, then we'll dance together.'

“But who on earth put it there? I didn't, I couldn't reach, nor could you, and anyhow you can't write yet. Mr. and Mrs. Beer wouldn't have, surely. Well, who did, Thomas?”

It was cold standing by the water, under the boughs of trees. And suddenly she felt rather frightened. She looked across at Thomas as he stood silently shaking his head.

“Who can it have been? Was it there yesterday?” Still he shook his head. She suddenly felt that the writer was here, crouching somewhere, peering through the new green leaves. She wanted to run, grab Thomas and run; but she mustn't panic in front of him, he mustn't see she was frightened, he was only a child.

“Come on, we'd better go in for lunch,” and she made herself walk slowly back to the house, up the little flight of steps, pushing between the dark rhododendron bushes whose pale green buds had pink linings. It was only writing, writing that hardly made sense. First we'll wait, then we'll whistle, then we'll dance together. But there was something ominous about it, about waiting turning to whistling turning to dancing, as though whoever had written it was going to -- increase.

Moon Eyes

Moon Eyes